美国历史:废奴运动 |

您所在的位置:网站首页 › 奴隶的意思英文 › 美国历史:废奴运动 |

美国历史:废奴运动

|

1833年4月在费城成立了全国性的美国反对奴隶制协会,总部设在纽约。随后反奴隶制协会在北部各地纷纷建立,到40年代这类组织约达2000个,参加协会人数超过20万人,形成声势浩大的群众运动。

Abolitionist Movement (废奴运动) The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation (解放) of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation (种族歧视和隔离). Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical (激进的、彻底的) abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor (热情) of the Second Great Awakening(席卷全国的大型宗教运动:第二次大觉醒), which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent (突出的) in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity (敌意、仇恨) between North and South leading up to the Civil War.

Thomas Jefferson The first attempts to end slavery in the British/American colonies came fromThomas Jeffersonand some of his contemporaries (同辈人、同代人). Despite the fact that Jefferson was a lifelong slaveholder (奴隶主), he included strong anti-slavery language in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence《独立宣言》, but other delegates took it out. Benjamin Franklin, also a slaveholder for most of his life, was a leading member of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the first recognized organization for abolitionists in the United States. Following the Revolutionary War, Northern states abolished slavery, beginning with the 1777 constitution of Vermont, followed by Pennsylvania's gradual emancipation act in 1780. As President, on 2 March 1807, Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slavesand it took effect (生效) in 1808.In 1820 he privately supported the Missouri Compromise, believing it would help to end slavery. He left the anti-slavery struggle to younger men after that.

From the 1830s until 1870, the abolitionist movement attempted to achieve immediate emancipation of all slaves and the ending of racial segregation and discrimination. Their propounding (提议) of these goals distinguished abolitionists from the broad-based political opposition to slavery’s westward expansion that took form in the North after 1840 and raised issues leading to the Civil War. Yet these two expressions of hostility (敌意) to slavery – abolitionism and Free-Soilism – were often closely related not only in their beliefs and their interaction but also in the minds of southern slaveholders who finally came to regard the North as united against them in favor of black emancipation.

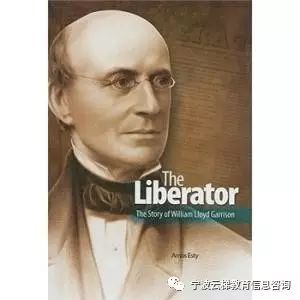

Although abolitionist feelings had been strong during the American Revolution and in the Upper South during the 1820s, the abolitionist movement did not coalesce (联合) into a militant crusade until the 1830s. In the previous decade, as much of the North underwent the social disruption associated with the spread of manufacturing and commerce, powerful evangelical (新教会的) religious movements arose to impart spiritual direction to society. By stressing the moral imperative to end sinful practices and each person's responsibility to uphold (支持、支撑) God's will in society, preachers like Lyman Beecher, Nathaniel Taylor, and Charles G. Finney in what came to be called the Second Great Awakening led massive religious revivals in the 1820s that gave a major impetus (动力、促进) to the later emergence of abolitionism as well as to such other reforming crusades as temperance (节制), pacifism (和平主义), and women's rights. By the early 1830s, Theodore D. Weld, William Lloyd Garrison, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, and Elizur Wright, Jr., all spiritually nourished by revivalism, had taken up the cause of “immediate emancipation.”

In early 1831, Garrison, in Boston, began publishing his famous newspaper, the Liberator, supported largely by free African-Americans, who always played a major role in the movement. In December 1833, the Tappans, Garrison, and sixty other delegates of both races and genders met in Philadelphia to found the American Anti-Slavery Society, which denounced (公开指责) slavery as a sin that must be abolished immediately, endorsed nonviolence, and condemned racial prejudice. By 1835, the society had received substantial moral and financial support from African-American communities in the North and had established hundreds of branches throughout the free states, flooding the North with anti-slavery literature, agents, and petitions (请愿) demanding that Congress end all federal support for slavery. The society, which attracted significant participation by women, also denounced the American Colonization Society’s program of voluntary gradual emancipation and black emigration.

All these activities provoked widespread hostile responses from North and South, most notably violent mobs (暴徒、犯罪团伙), the burning of mailbags containing abolitionist literature, and the passage in the U.S. House of Representatives of a “gag rule”(禁止对某个问题进行公开评论的规定) that banned consideration of antislavery petitions. These developments, and especially the 1837 murder of abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy, led many northerners, fearful for their own civil liberties, to vote for anti-slavery politicians and brought important converts (转变) such as Wendell Phillips, Gerrit Smith, and Edmund Quincy to the cause. But as antislavery sentiment (情绪) began to appear in politics, abolitionists also began disagreeing among themselves. By 1840 Garrison and his followers were convinced that since slavery’s influence had corrupted all of society, a revolutionary change in America’s spiritual values was required to achieve emancipation. To this demand for “moral suasion,” (劝告) Garrison added an insistence on equal rights for women within the movement and a studious avoidance of “corrupt” political parties and churches. To Garrison’s opponents, such ideas seemed wholly at odds with (和。。。不一致/不符) Christian values and the imperative to influence the political and ecclesiastical (基督教会的) systems by nominating and voting for candidates committed to abolitionism. Disputes over these matters split the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1840, leaving Garrison and his supporters in command of that body; his opponents, led by the Tappans, founded the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Meanwhile, still other foes (敌人、反对者) of Garrison launched the Liberty party with James G. Birney as its presidential candidate in the elections of 1840 and 1844.

Although historians debate the extent of the abolitionists’ influence on the nation’s political life after 1840, their impact on northern culture and society is undeniable. As speakers,Frederick Douglass, Wendell Phillips, and Lucy Stonein particular became extremely well known. In popular literature the poetry of John Greenleaf Whittier and James Russell Lowell circulated widely, as did the autobiographies of fugitive slaves such as Douglass, William and Ellen Craft, and Solomon Northrup. Abolitionists exercised a particularly strong influence on religious life, contributing heavily to schisms (教会分裂) that separated the Methodists (1844) and Baptists (1845), while founding numerous independent antislavery “free churches.” In higher education abolitionists founded Oberlin College, the nation’s first experiment in racially integrated coeducation, the Oneida Institute, which graduated an impressive group of African-American leaders, and Illinois’s Knox College, a western center of abolitionism.

Within the Garrisonian wing of the movement, female abolitionists became leaders of the nation’s first independent feminist movement, instrumental (起重要作用的) in organizing the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.Although African-American activists often complained with reason of the racist and patronizing behavior of white abolitionists, the whites did support independently conducted crusades by African-Americans to outlaw (宣布。。。不合法) segregation and improve education during the 1840s and 1850s. Especially after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law (1850年逃亡奴隶法的通过), white abolitionists also protected African-Americans threatened with capture as escapees from bondage (奴役、束缚), although blacks themselves largely managed the Underground Railroad. By the later 1850s, organized abolitionism in politics had been subsumed (纳入。。。之中) by the larger sectional crisis over slavery prompted by the Kansas-NebraskaAct, the Dred Scottdecision, and John Brown’s raid (突袭、袭击) on Harpers Ferry. Most abolitionists reluctantly supported the Republican party, stood by the Union in the secession crisis (分离危机), and became militant champions of military emancipation during the Civil War. The movement again split in 1865, when Garrison and his supporters asserted that the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment(第十三条修正案) abolishing slavery made continuation of the American Anti-Slavery Society unnecessary. But a larger group led by Wendell Phillips, insisting that only the achievement of complete political equality (政治平等) for all black males could guarantee the freedom of the former slaves, successfully prevented Garrison from dissolving (分裂) the society. It continued until 1870 to demand land, the ballot (纸式投票), and education for the freedman.

Civil War and Final Emancipation Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation(奴隶解放宣言) was an executive order of the U.S. government issued on 1 January 1863, changing the legal status of 3 million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free". Slaves were legally freed by the Proclamation and became actually free by escaping to federal lines, or by advances of federal troops. Many served the federal army as teamsters (卡车司机), cooks, laundresses and labourers. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible out of reach of the Union army. By "Juneteenth" (19 June 1865, in Texas), the Union Army (联盟军) controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all its slaves. The owners were never compensated (补偿、赔偿).

The border states (交界南部诸州—美国南北战争前的诸合法蓄奴州,包括特拉华、肯塔基、马里兰、密苏里和西弗吉尼亚诸州等)were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation, but they too (except Delaware) began their own emancipation programmes. When the Union Army entered Confederate areas, thousands of slaves escaped to freedom behind Union Army lines, and in 1863 many men started serving as the United States Colored Troops. The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution took effect in December 1865 and finally ended slavery throughout the United States. It also abolished slavery among the Indian tribes (部落、部族), including the Alaska tribes that became part of the U.S. in 1867.

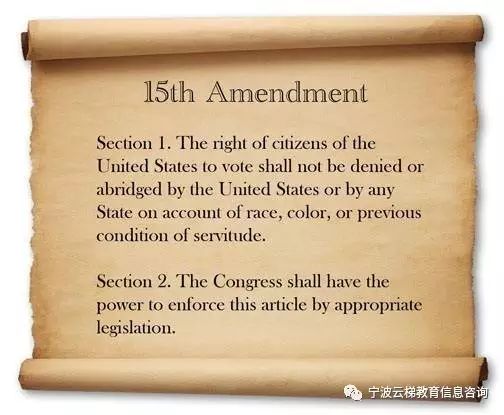

Only when the Fifteenth Amendmentextending male suffrage (投票权) to African-Americans was passed did the society declare its mission completed. Traditions of racial egalitarianism (种族平等主义) begun by abolitionists lived on, however, to inspire the subsequent founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (全国有色人种促进会的建立) in 1909.

|

【本文地址】

今日新闻 |

推荐新闻 |

返回搜狐,查看更多

返回搜狐,查看更多