Frontiers |

您所在的位置:网站首页 › 3a:4b:5c › Frontiers |

Frontiers

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol., 06 April 2023Sec. Evolutionary and Genomic Microbiology

Volume 14 - 2023 |

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1143648

Gut microbiota from sigma-1 receptor knockout mice induces depression-like behaviors and modulates the cAMP/CREB/BDNF signaling pathway  Jia-Hao Li1†, Jia-Hao Li1†,  Jia-Li Liu1†, Jia-Li Liu1†,  Xiu-Wen Li1, Xiu-Wen Li1,  Yi Liu1, Yi Liu1,  Jian-Zheng Yang1, Jian-Zheng Yang1,  Li-Jian Chen1, Li-Jian Chen1,  Kai-Kai Zhang1, Kai-Kai Zhang1,  Xiao-Li Xie2* and Xiao-Li Xie2* and  Qi Wang1* 1Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Forensic Multi-Omics for Precision Identification, School of Forensic Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China 2Department of Toxicology, School of Public Health, Southern Medical University (Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Tropical Disease Research), Guangzhou, Guangdong, China Qi Wang1* 1Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Forensic Multi-Omics for Precision Identification, School of Forensic Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China 2Department of Toxicology, School of Public Health, Southern Medical University (Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Tropical Disease Research), Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

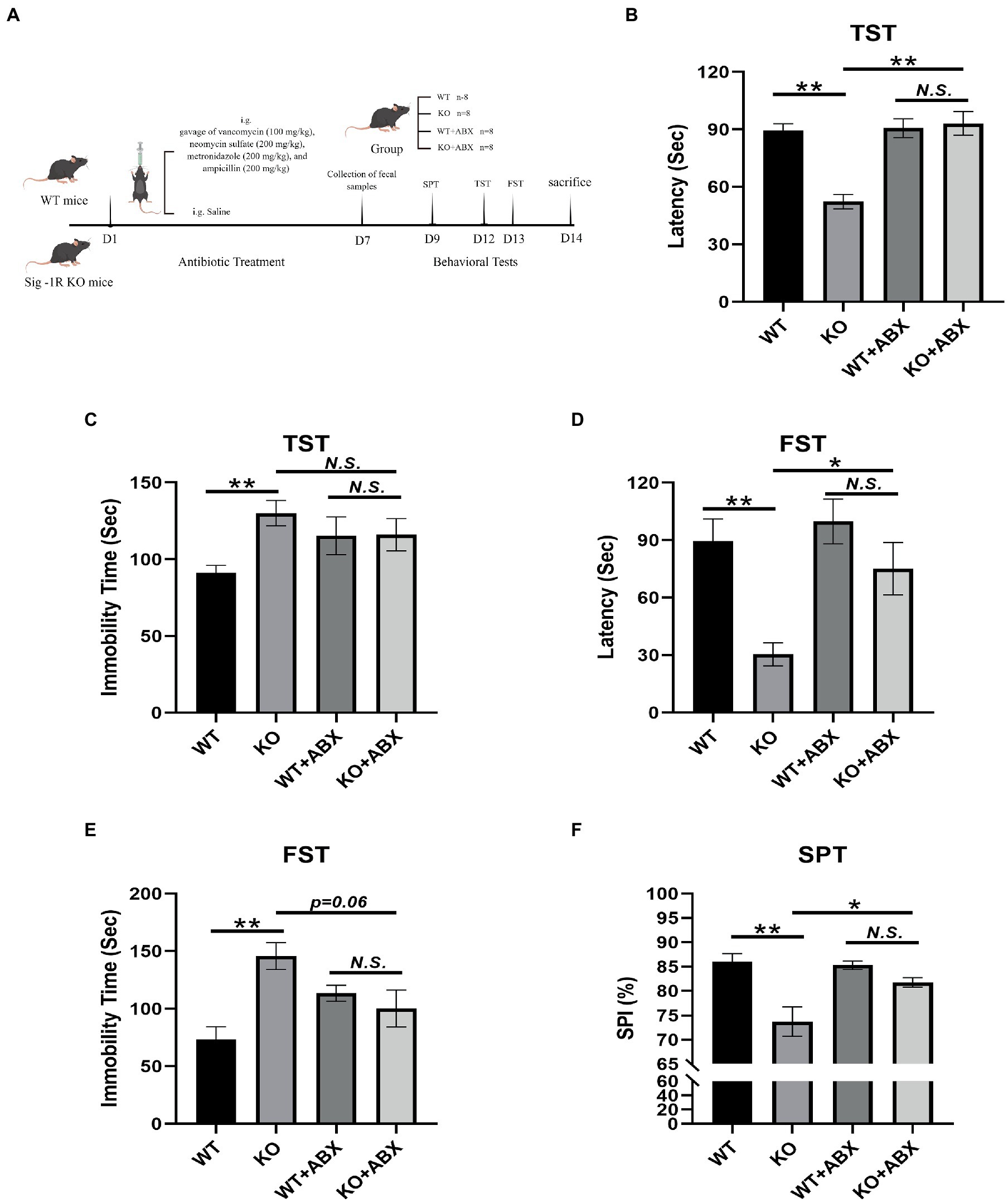

Introduction: Depression is a common mental disorder that affects approximately 350 million people worldwide. Much remains unknown about the molecular mechanisms underlying this complex disorder. Sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R) is expressed at high levels in the central nervous system. Increasing evidence has demonstrated a close association between the Sig-1R and depression. Recently, research has suggested that the gut microbiota may play a crucial role in the development of depression. Methods: Male Sig-1R knockout (Sig-1R KO) and wild-type (WT) mice were used for this study. All transgenic mice were of a pure C57BL/6J background. Mice received a daily gavage of vancomycin (100 mg/kg), neomycin sulfate (200 mg/kg), metronidazole (200 mg/kg), and ampicillin (200 mg/kg) for one week to deplete gut microbiota. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was conducted to assess the effects of gut microbiota. Depression-like behaviors was evaluated by tail suspension test (TST), forced swimming test (FST) and sucrose preference test (SPT). Gut microbiota was analyzed by 16s rRNA and hippocampal transcriptome changes were assessed by RNA-seq. Results: We found that Sig-1R knockout induced depression-like behaviors in mice, including a significant reduction in immobility time and an increase in latency to immobility in the FST and TST, which was reversed upon clearance of gut microbiota with antibiotic treatment. Sig-1R knockout significantly altered the composition of the gut microbiota. At the genus level, the abundance of Alistipes, Alloprevotella, and Lleibacterium decreased significantly. Gut microbiota dysfunction and depression-like phenotypes in Sig-1R knockout mice could be reproduced through FMT experiments. Additionally, hippocampal RNA sequencing identified multiple KEGG pathways that are associated with depression. We also discovered that the cAMP/CREB/BDNF signaling pathway is inhibited in the Sig-1R KO group along with lower expression of neurotrophic factors including CTNF, TGF-α and NGF. Fecal bacteria transplantation from Sig-1R KO mice also inhibited cAMP/CREB/BDNF signaling pathway. Discussion: In our study, we found that the gut-brain axis may be a potential mechanism through which Sig-1R regulates depression-like behaviors. Our study provides new insights into the mechanisms by which Sig-1R regulates depression and further supports the concept of the gut-brain axis. 1. IntroductionDepression, also known as major depressive disorder (MDD), is a common mental disorder that affects approximately 350 million people worldwide. The causes of depression are thought to be multifaceted and may involve both genetic and environmental factors (Malhi and Mann, 2018). In the past few decades, various theories about the development of depression have been proposed, including the inflammation hypothesis, the neural circuits hypothesis, the neurotransmitter hypothesis, and the neurotrophic hypothesis (López-Figueroa et al., 2004; Duman and Monteggia, 2006; Fujimoto et al., 2008; Maes, 2008). The neurotrophic hypothesis suggests that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and other neurotrophic factors may be involved in the development of depression, and reductions in BDNF have been linked to atrophy of brain regions involved in emotion, such as the hippocampus (Castren and Rantamaki, 2010). Neurotrophic factor BDNF has also turned out to be significantly associated with depression in clinical patients and in extensive studies. In recent years, the neurotrophic hypothesis has become an important target of novel antidepressant drugs (Wang A. et al., 2021). Despite significant progress in our understanding of depression, much remains unknown about the molecular mechanisms underlying this complex disorder. Sigma-1 receptor is a protein encoded by the SIGMAR1 gene. Sig-1R is expressed at high levels in the central nervous system and has been shown to have neuroprotective effects (Wu et al., 2021). Mutations in the SIGMAR1 gene have been linked to an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and are strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Fehér et al., 2012). In addition, two studies have found that Sig-1R may be involved in the development of depression through its effects on neurotrophic and growth factor signaling pathways (Kishi et al., 2010; Mandelli et al., 2017; Stiernstromer et al., 2022). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a moderate affinity for Sig-1Rs and the antidepressant effect of SSRIs may be mediated by Sig-1R (Smith and Su, 2017; Izumi et al., 2023). Efficacy of fluvoxamine treatment in improving psychotic symptoms and depressive symptoms is dose-dependently related to its binding to Sig-1Rs in the healthy human brain (Hashimoto, 2009). One potential mechanism through which Sig-1R may exert its neuroprotective effects is by promoting brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression. For example, Sig-1R agonists have been shown to reverse the downregulation of BDNF and improve symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Ji et al., 2017). Another Sig-1R agonist has been demonstrated to have neuroprotective effects in a mouse model of alpha-thalassemia X-linked intellectual disability (Yamaguchi et al., 2018). The brain’s BDNF protein was elevated by chronic antidepressant treatment, including SSRIs (Hashimoto, 2010). Activation of Sig-1R enhanced the conversion of pro-BDNF to mature BDNF, as well as the release of mature BDNF into the extracellular space (Fujimoto et al., 2012; Hashimoto, 2013). These pieces of evidence suggest that activation of the Sig-1R promotes chaperone activity, which influences BDNF secretion, exerting antidepressant-like effects. Despite these advances, the exact role of Sig-1R in the development of depression is not yet fully understood. The relationship between gut microbiota and depression has garnered increasing attention in recent years, with a growing body of evidence demonstrating a significant association between the two. Studies have found that the gut microbiota of individuals with depression differs significantly from that of healthy individuals (Jiang et al., 2015; Aizawa et al., 2016). Moreover, transplanting the microbiota from depressed individuals into germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice has resulted in the induction of symptoms similar to depression (Kelly et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019). These findings suggest that the gut microbiota may play a role in the pathogenesis of depression. Despite the growing evidence linking Sig-1R to depression, the precise role of Sig-1R in this disorder remains unknown. To further understand the involvement of Sig-1R in depression, we conducted a study in which we compared depression-like behaviors in the wild-type (WT) and Sig-1R knockout (KO) groups. We also explored the role of gut microbiota in these behaviors through antibiotic treatment and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Our results showed that Sig-1R knockout mice exhibited increased depression-like behaviors and significant changes in gut microbiota. The gut microbiota of Sig-1R knockout mice was sufficient to induce an increase in depression-like behaviors. These effects may be mediated by a reduction in neurotrophic factors through the cAMP/CREB/BDNF signaling pathway. Our study provides new insights into the mechanisms by which Sig-1R may contribute to the development of depression. 2. Materials and methods 2.1. AnimalsDuring the study, the animals were kept in specific pathogen-free conditions in the laboratory animal center of Southern Medical University, with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Sig-1R knockout mice were obtained from Cyagen Biosciences. All transgenic mice were of a pure C57BL/6 J background. Sig-1R knockout mice and WT mice, identified by PCR genotyping (Supplementary Figure 1), were generated by breeding Sig-1R heterozygous mice with Sig-1R heterozygous mice. WT littermates of the same sex were used as controls in all experiments. Feces were collected from 10-week-old mice and behavioral tests were conducted. As for the collection of fresh fecal samples, mice were placed in a cage covered with autoclaved paper in a SPF environment and allowed to defecate freely between 9:00 and 11:00 AM. The fecal samples were collected using autoclaved RNA-free EP tubes, and then stored in −80°C until used. A total of three fecal samples were collected. From 7:00 PM onward, following euthanasia, serum and hippocampal tissue were collected for further analysis. Samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. 2.2. Antibiotic treatmentA flowchart of the modeling process is shown in Figure 1A. WT and Sig-1R knockout mice were divided into four groups (n = 8 per group): WT, WT + ABX, KO, and KO + ABX. Antibiotic treatment was conducted as described previously (Chen L. et al., 2021). Briefly, 8–9-week-old mice received a daily gavage of vancomycin (100 mg/kg), neomycin sulfate (200 mg/kg), metronidazole (200 mg/kg), and ampicillin (200 mg/kg) for 1 week. This dose of antibiotic treatment depletes the gut microbiota without causing animal death. The behavioral experiments and sample processing methods were the same as described above. FIGURE 1

Figure 1. Antibiotic treatment reverses Sig-1R knockout-induced depression-like behaviors. (A) The ABX treatment flowchart by Figdraw. (B) Latency (s) to immobility in the TST [For ABX treatment, F(1, 13) = 11.50, p = 0.0048, two-way ANOVA]. (C) Immobility time (s) in the TST [For ABX treatment, F(1, 13) = 6.068, p = 0.0285, two-way ANOVA]. (D) Latency (Sec) to immobility in the FST [For ABX treatment, F(1, 13) = 5.950, p = 0.0298, two-way ANOVA]. (E) Immobility time (s) in the FST [For ABX treatment, F(1, 13) = 13.37, p = 0.0029, two-way ANOVA]. (F) The sucrose preference index (SPI) in the SPT [For ABX treatment, F(1, 10) = 37.09, p = 0.0001, two-way ANOVA]. **p |

【本文地址】